The following was written by ICBA Chief Economist Jock Finlayson:

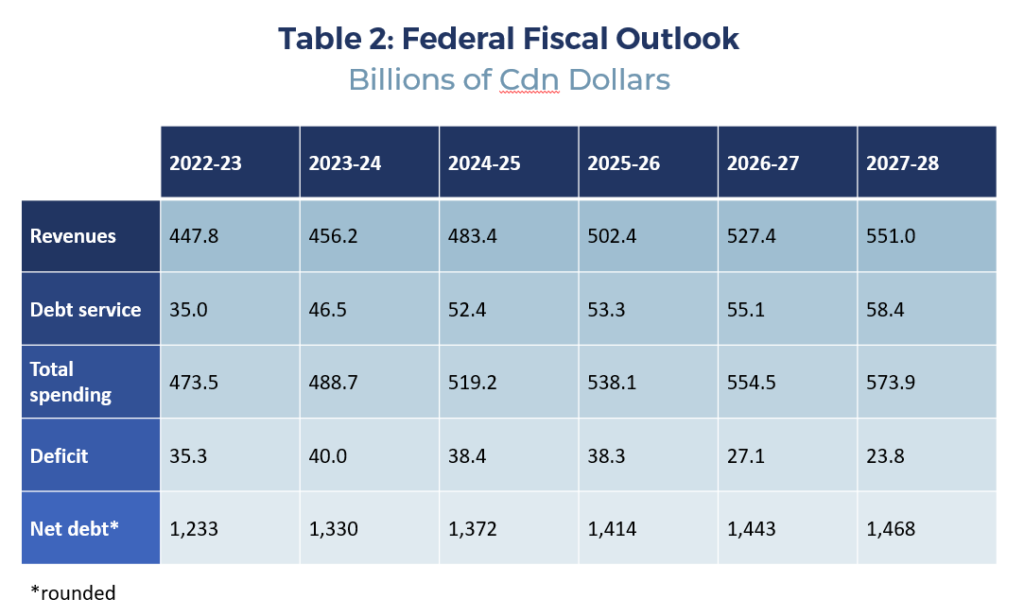

There were few surprises in the Fall 2023 Economic Statement delivered by federal Finance Minister Crystia Freeland on November 21.[1] The Liberal government is not deviating from its well-established penchant for hefty spending hikes and endless budget deficits. Based on the revised forecast presented by the Minister, federal policymakers are planning for a steady flow of red ink over the balance of the decade, notwithstanding the huge increase in debt caused by the 2020-21 COVID-induced hit to Canada’s public finances. Compared to the fiscal outlook in the spring 2023 Budget, the government is now expecting to spend another $8 billion or so every year from 2024-25 through 2027-28. This means bigger operating deficits and a larger debt than the Finance Minister was projecting only several months ago.

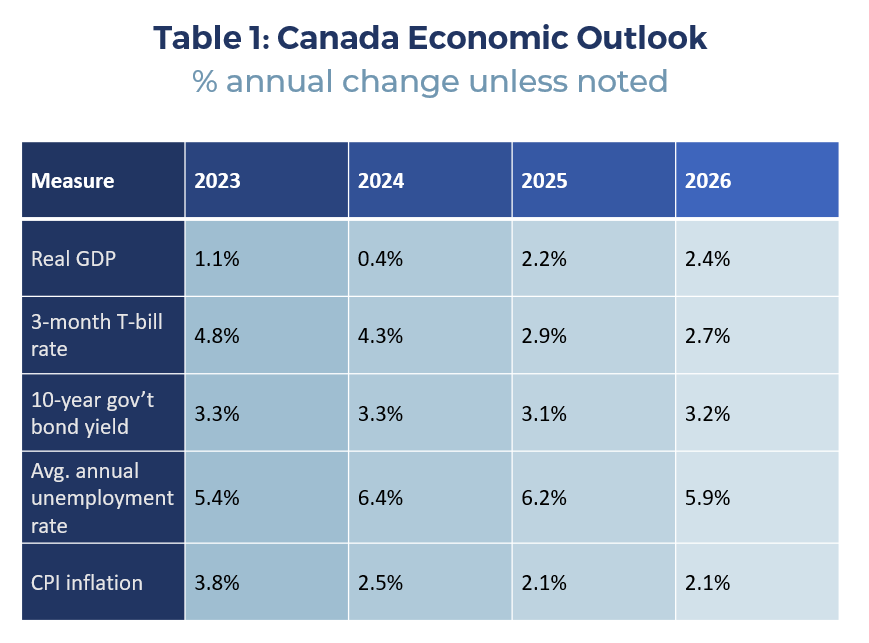

The Trudeau years will be known as a time of rapid debt accumulation. Whereas Ottawa’s net debt amounted to about 30% of Canada’s GDP when Mr. Trudeau assumed office in 2015, today it stands at over 42%. And if the economy underperforms the relatively optimistic forecasts being used by Minister Freeland, the debt/GDP ratio could very well rise further. In particular, we suspect the government’s future cost of borrowing could easily be higher than the relatively low 3.1-3.3% rates assumed for 10-year government bonds in the Economic Statement (see Table 1).

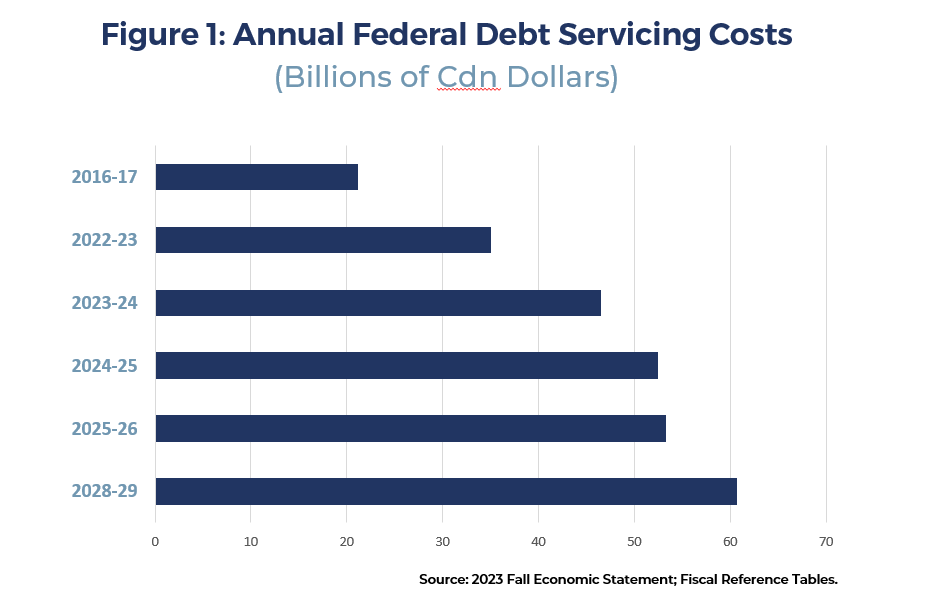

As the Minister noted, Canada’s federal debt remains manageable by the standards of several other advanced economy jurisdictions, including the U.S. However, in a world of higher interest rates and continuous deficits, the cost of servicing Ottawa’s $1.2 trillion debt is increasing sharply. Annual public debt charges will more than double by the end of the decade – climbing from around $30 billion in 2021 to perhaps $65 billion by 2030 (see Figure 1 below).[2] (Back in 2016, federal debt servicing expenses were in the vicinity of $20 billion.) The growing cost of servicing the debt could put upward pressure on taxes. And it may leave the federal government with a diminished capacity to respond to future shocks.

Table 2 reports the fiscal projections in the Fall Economic Statement.

Higher spending and the mounting debt have made it harder for the Bank of Canada to get inflation back to 2%, after three years (2021-23) during which the all-items Consumer Price index has been running well above the Bank’s target. In this sense, fiscal and monetary policy in Canada have been misaligned for at least the last 18 months: the central bank has been seeking aggressively to temper demand and dampen economy-wide spending, while policymakers in Ottawa, Victoria and some other provincial capitals have been pouring money into an economy that doesn’t require additional “stimulus” — in pursuit of a mix of political, social and environmental objectives, including, most recently, a perceived need to address the cost of living challenges facing Canadians.

Meanwhile, the Trudeau government seemingly has few ideas for fixing Canada’s business investment crisis. ICBA believes the word “crisis” is fully warranted: as documented in a new C.D. Howe Institute study,[3] Canadian businesses are investing only 58% as much as their American counterparts, measured on a per employee basis, with the share trending lower in the last decade. That means Canada is underinvesting in the plant and equipment, machinery, digital and other technologies, software, engineering and other physical infrastructure, and intellectual property products needed to boost productivity and real wages, expand the economy’s productive capacity, and connect Canadian businesses to global markets. The Economic Statement is silent on the problem of weak business investment.

As it happens, Canada’s investment landscape is about to become even less competitive, with the accelerated depreciation rules that Ottawa adopted back in 2018 due be phased out starting in January 2024. The Economic Statement could usefully have pledged to leave the existing depreciation rules in place, but it did not. Instead, the government is doubling down on its “green industrial strategy,” which features hitherto unimaginable subsidies and tax incentives directed at a small sub-set of Canadian industries. In our view, that strategy is destined to disappoint, not least because the sectors in line for the bulk of Ottawa’s largesse make up only 3% of the economy, according to data released by Statistics Canada a few weeks ago. Massive subsidies and rich incentives targeted at a small slice of the economy won’t do much to bolster overall business investment or spur faster productivity growth.

A Few Specifics Affecting Construction

ICBA welcomes measures to expand housing supply – particularly rental – as well as the government’s efforts to convince municipalities to embrace densification and reduce barriers to new development across a spectrum of housing types. We also applaud the federal government’s recent decision to remove the GST from new purpose-built rental housing. The Economic Statement earmarks more money for affordable rental housing, both directly and via CMHC programs. Over time, should have a modest positive impact on the availability of rental units.

However, the housing demand-supply gap in Canada is enormous: based on expected population growth, CMHC estimates the country would need 3.5 million additional dwelling units – over and above the recent rate of construction — by the end of the decade to restore “affordability”. At present, annual housing starts are running around 250-270k, dramatically short of what’s necessary to realize the goal of affordability as per the CMHC’s analysis. This suggests the steps taken and proposed by Ottawa – both in the 2023 Fall Economic Statement and earlier — will have little near-term impact on housing supply and likely prove insufficient to significantly move the dial on housing affordability, even in the medium term.

Some housing advocates and politicians overlook the fact that Canada is primarily a market-driven economy, where the private sector produces most of the goods and services demanded and consumed by Canadians. This includes the vast majority of new and redeveloped housing. Government cannot solve Canada’s housing crisis. If they want to tackle today’s complex housing supply and affordability challenges, Canadian policymakers at all levels must commit to increased collaboration with the development, construction and financial service industries. Investors, builders, developers, and contractors are not obstacles to achieving more affordable housing in Canada; they are its enablers, particularly if the right public policies are in place.

Finally, the Fall Economic Statement recognizes the need to expand Canada’s skilled workforce. Smart immigration policy can help. In May 2023, the government announced a new selection process under the Express Entry immigration system to prioritize permanent residency applicants with specific skills. ICBA believes more can and should be done to better align immigrant selection with current/projected worker shortages, occupation-focused retirement forecasts, and labour market demand. In particular, we recommend that the government commit to admit up to 10,000 additional immigrants with experience and skills relevant to the construction industry by 2025.

[1] Finance Canada, 2023 Fall Economic Statement, November 21, 2023.

[2] Ibid, p. 77. For the debt servicing cost in 2021 and earlier, see Department of Finance, Fiscal Reference Tables, October 2023.

[3] William Robson and Mawakina Bafale, Working Harder for Less: More People but Less Capital is No Recipe for Prosperity, C.D. Howe Institute, November 7, 2023.