The following was written by ICBA Chief Economist Jock Finlayson.

Statistics Canada recently published revised data on economic growth covering the period 2021-22. Overall, the picture was positive, notably for Western Canada, as the economy rebounded from the worst of the COVID pandemic in 2020.

Nationally, the value of output (gross domestic product, or GDP) adjusted for inflation expanded by 3.8% last year, on the heels of a 5.3% increase in 2021. Economic activity across Canada continued to “normalize” after the shock of 2020.

Consumer spending on services fell steeply when COVID first hit, but it has revived since then, powering a solid 5.1% gain in real household expenditures in 2022. Non-residential construction was up 6.7% (after inflation) last year, with Alberta and B.C. making major contributions to the national advance – mainly thanks to major projects in the oil and gas, utilities, and pipeline industries. After a near-record increase in residential investment in 2021, this category of spending lost its mojo in 2022, dipping by 12% amid escalating interest rates and borrowing costs — despite strong underlying housing demand from a rapidly growing population.

Meanwhile, governments in Canada won the fiscal lottery in 2022, in large part because of higher-than-anticipated inflation. Surging inflation fueled faster growth in “nominal” gross domestic product, which in turn boosted the tax base on which governments rely for revenues from income, sales, energy, property, and payroll taxes. Last year, Canada’s nominal GDP jumped by an outsized 11.8% (in 2021, it increased by 13.4%), aided by an inflation rate of almost 7%, bolstering tax collections and allowing the provinces to report healthier public finances. Unfortunately, that fiscal improvement is destined to be temporary, as nominal GDP growth is now decelerating, public sector payroll costs are set to soar, and some governments have chosen to keep the spending taps wide open even with the return of large deficits.

Focus on Western Canada

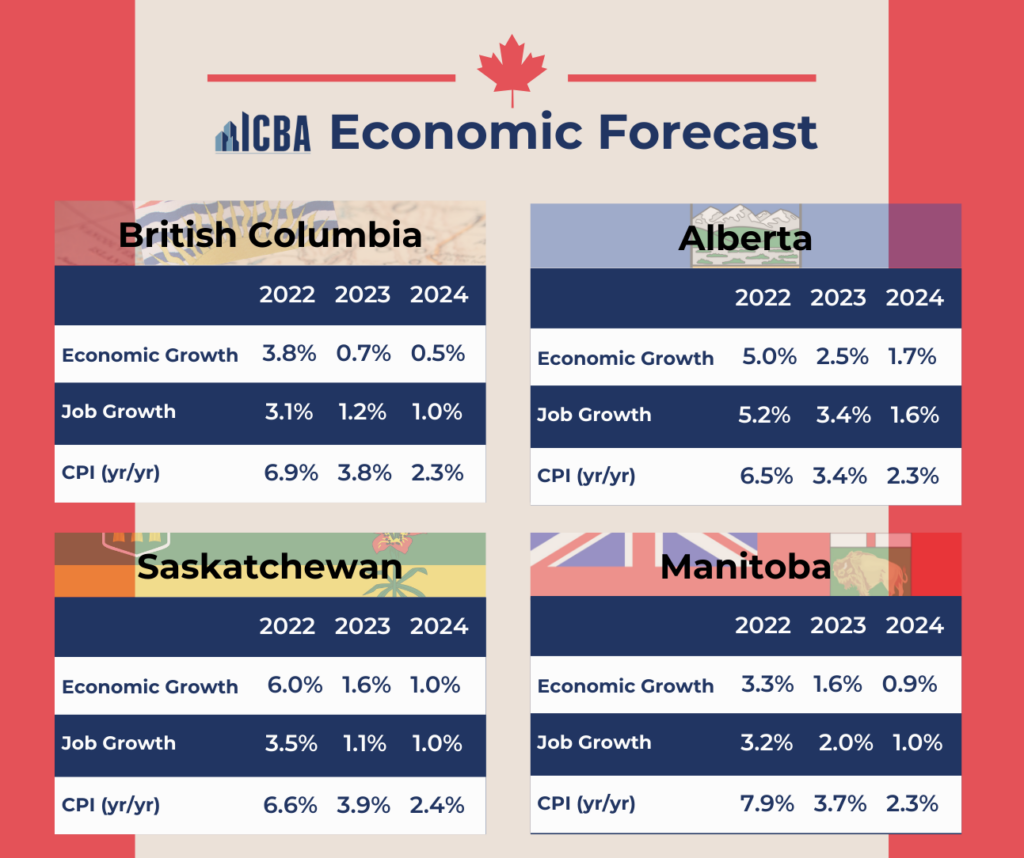

The four Western provinces had a good year in 2022 (see Figure 1). Real GDP gains ranged from 6.0% in Saskatchewan to 3.8% in B.C. – with the latter figure matching the national growth rate. Labour markets were buoyant across the region, boosting employment and aggravating worker shortages in several industries, including construction. Rising in-migration to Alberta and B.C. and high levels of construction and project-based investment in the industrial, commercial, engineering, and institutional segments helped to underpin the economic growth story. A rebound in energy and other commodity prices also played a role.

However, over the course of 2023 economic momentum has visibly waned in Canada, as consumers and businesses have struggled with much higher interest rates, record levels of debt, and fast-rising living and business operating costs. Slower global growth has also affected many export-oriented industries in Western Canada. The economic downshifting is evident in the year-to-date numbers for job creation, consumer spending, housing sales, and exports.

Looking ahead, we believe the economic slowdown unfolding in 2023 will carry into next year, with all four Western provinces likely to see slower GDP and employment growth compared to 2022-23. In part, this reflects the lagged effects of the higher interest rates that took hold over the last 20 months. Fortunately, inflation in Canada has fallen significantly, suggesting that interest rates have peaked. We expect the Bank of Canada to start easing monetary policy by the spring of next year.

Table 1 provides ICBA Economics’ preliminary projections for the Western provinces in 2023 and our initial forecast for 2024.

British Columbia will put in the weakest economic performance over 2023-24, while Alberta is positioned to lead the region (and likely Canada) in the growth of GDP, employment, and consumer spending.

Alberta stands to gain from strong in-migration and increases in the volume of oil production and exports. A number of large industrial projects will also inject some pep into the economy. Last year, Alberta’s energy exports reached $160 billion. Softer energy markets point to a dip in the value of oil and gas exports in 2023 – which is likely to extend into next year. Still, rising energy production and investment spending should be very positive for the province’s economy in the next few years.

B.C. is in a less favourable position. A handful of massive multi-year energy-related projects — collectively involving a cumulative $90-100 billion of capital outlays — are now winding down, heralding a sizable fall-off in non-residential investment in 2024-25. At the same time, B.C.’s economically important forest industry is struggling with an uncompetitive domestic policy and operating environment, while the manufacturing and transportation sectors concentrated in the lower mainland are hampered by high costs, skill shortages, and severe constraints on the availability of industrial land. On a brighter note, B.C. can look forward to a further recovery of international tourism in 2024. It’s also benefitting from a growing advanced technology cluster and the recent re-opening of the local film and television production industry following the settlement of a lengthy labor dispute in California. High levels of international in-migration — partially offset by net interprovincial out-migration — will continue to act an economic tailwind. However, measured on a per person basis, British Columbia’s real GDP will be shrinking over 2023-24, pointing to an erosion of overall prosperity.