By Jock Finlayson, ICBA Chief Economist

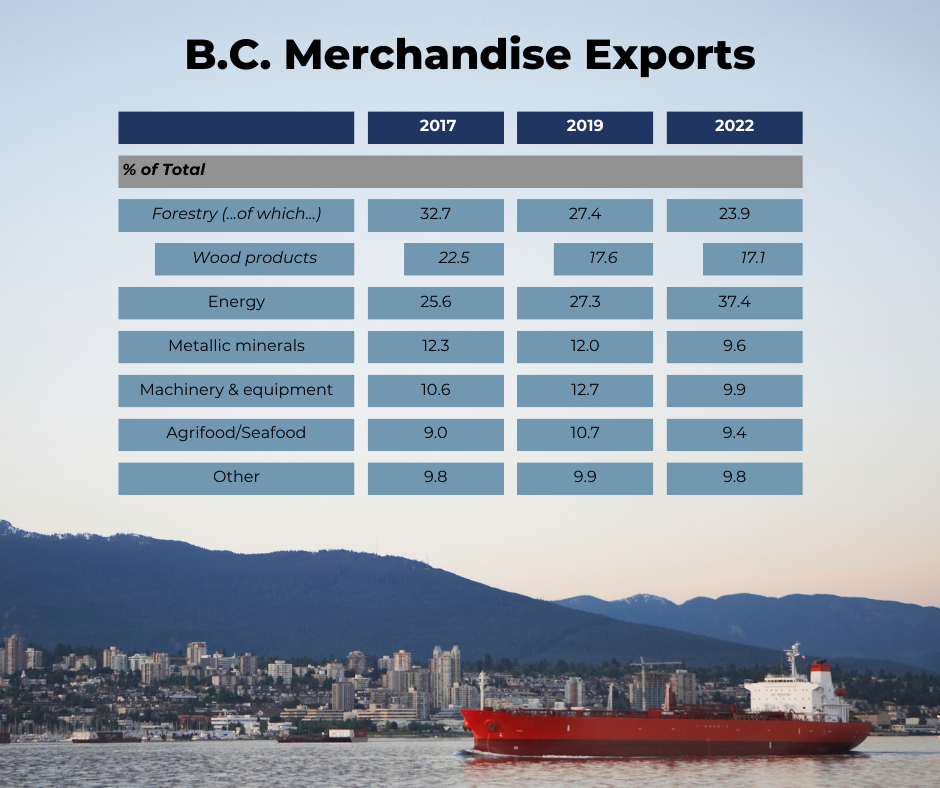

The forest products sector has long served as both B.C.’s leading source of exports and a foundation for jobs and other economic activity across the province. So, I was delighted to accept an invitation from the Truck Loggers Association of B.C. to speak on the topic of “bringing prosperity to the forest industry” at the Association’s convention in Vancouver earlier this month. TLA is a key advocacy and benefits partner with ICBA. And the economic health of all of the interrelated parts of the forest industry – logging contractors, wood products manufacturers, and pulp and paper companies — matters to the B.C. construction sector, particularly given forestry’s still substantial economic footprint:

In reviewing trends affecting forestry over the past decade, I was shocked by the magnitude of the drop in timber harvesting in British Columbia. Much of this reflects fallout from the pine beetle infestation that devastated the lodgepole pine forest in the B.C. Interior in the early to mid-2000s. The beetle destroyed a sizable fraction of the previously accessible fibre supply in the affected areas. In addition, severe summer wildfire seasons over the past few years have added to the downward pressure on the timber supply.

However, government policy has also contributed to the sharp decline in timber harvesting which, in turn, has reduced the supply of logs and other raw materials needed by lumber manufacturers and pulp and paper mills in B.C. As a consequence, not only has the upstream logging industry been badly hurt by curtailed harvesting – the commercial viability of the wood products and pulp and paper segments of the larger industry has also been put at risk by a mix of “natural” and “policy-driven” developments.

The following summarizes what’s happened to forestry in B.C. since the mid-2010s. It makes for painful reading.

- Massive declines in the annual timber harvest – from 70 million cubic metres in 2012-14 to roughly 40 million cubic metres by 2022. Harvesting on “public lands” – lands owned by the Crown, which account for the vast majority of all forested land in the province – has plunged from 60 million cubic metres in 2018 to 35 million cubic metres last year.

- Meanwhile, actual volumes of timber harvested from public lands have fallen well below the volumes officially approved by the Ministry of Forests. In 2023, the harvest was 40% lower than the annual allowable cut (AAC) set by the government, according to tracking by the B.C. Council of Forest Industries.

- It is discouraging to see that B.C. has become the highest-cost lumber producing region in North America:

- With harvest levels plummeting and production costs rising, dozens of B.C. sawmills have closed or taken extended downtime, leading to tens of thousands of job losses and more than a few devastated forestry-dependent communities. Some pulp and paper mills have also been shuttered or forced to take downtime as the supply of pulp logs has dwindled and the cost of production in B.C. has risen due in part to escalating energy and carbon costs.

- The leading B.C.-based forest companies increasingly have been investing and seeking to expand their business footprints elsewhere – in other provinces, the U.S., and even Sweden. Even so, four of the top ten North American lumber producers are still B.C.-based companies:

What role has the B.C. government played in the forest industry’s unprecedented troubles? Essentially, the province has prioritized conservation values and other environmental objectives and downplayed the importance of sustaining an economically viable and competitive forest industry. Since 2017, the government has made a series of policy and regulatory decisions that have had the effect of slashing timber harvesting. In turn, this inevitably has led to a smaller fibre supply and higher raw materials costs for B.C. wood products manufacturers as well as pulp and paper mills, setting the stage for the cascade of mill closures referenced above.

Specifically, B.C. government policies that have contributed to the economic crisis afflicting forestry include sweeping deferrals of logging in “old growth” forests; the continued expansion of parks and protected areas; measures to safeguard the habitat of the mountain caribou; and various legislative changes (Bills 23, 28 and 41) affecting forest landscape planning, the issuance of cutting permits, and other aspects of forestry operations. Late last year, the government published a draft Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health Framework intended to shape future forest policy decisions. The proposed framework, if adopted, is likely to pave the way for a further dramatic decline in harvesting levels, additional mill closures, and higher day-to-day operating costs.

It is not that all of the steps taken by the province were ill-considered or unnecessary. Rather, the issue is the cumulative impact of a series of often far-reaching policy changes on an industry that is still a major source of export earnings and serves as the economic mainstay of dozens of communities in every region of the province.

Ultimately, provincial policymakers have overlooked the commercial needs and economic benefits that flow from the presence of a significant, globally competitive B.C. forest products industry. ICBA believes the balance among the sometimes-conflicting objectives that necessarily shape forest policy – particularly in a jurisdiction where the Crown owns most of the resource — has been lost. It is time to recalibrate the overall forest policy framework to put a higher priority on maintaining and expanding fibre supply, improving the industry’s cost competitiveness, and ensuring that the B.C. based companies that have been key to building the sector continue to be an important part of our business community.