By Jock Finlayson, ICBA Chief Economist

At a time when affordability and the cost of living have emerged as top-of-mind issues for many Canadians, it makes sense to take a quick look at the “other side” of the affordability equation: incomes.

Income comes from a few sources: employment (by far the biggest source), government transfers to families and individuals, and investment and rental income. To get a clear idea of the dollars available to households, we need to deduct direct taxes (income taxes and the employee-paid portion of payroll taxes) and also adjust for inflation when looking at how incomes change over time.

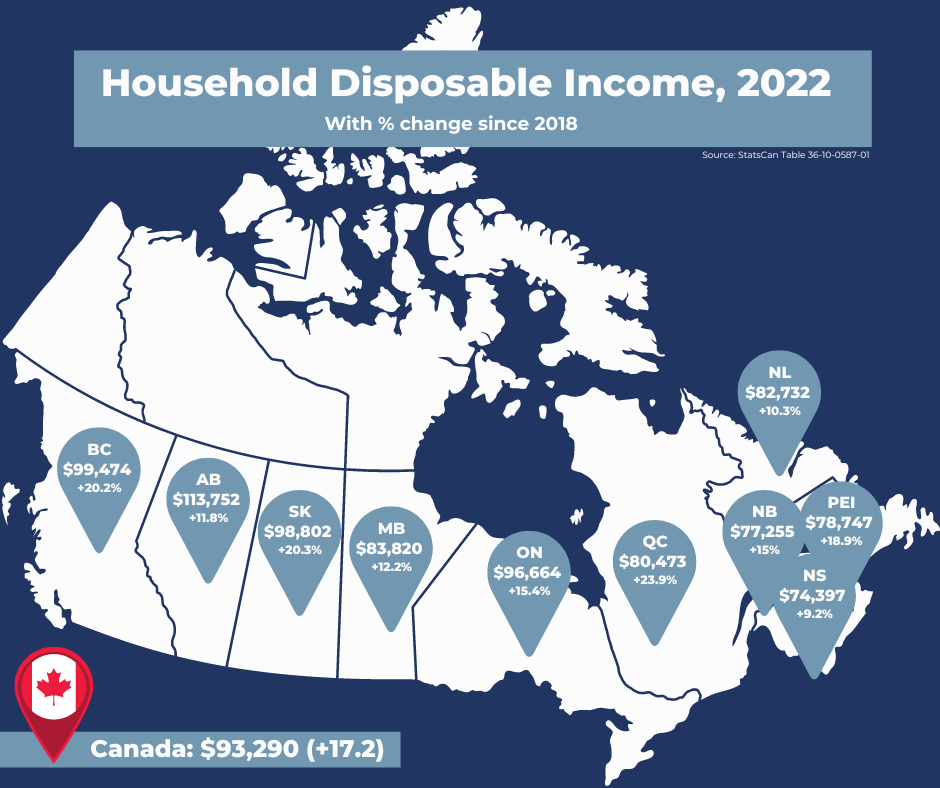

According to Statistics Canada, after-tax income for the typical Canadian household stood at $93,290 in 2022. (Households include both two or more people living under one roof and single individuals.) There are dramatic differences among the provinces on this key measure of economic well-being. Alberta is easily the richest province, with an after-tax household income of $113,572 in 2022 – 22% higher than the national average. B.C. ranked second, at $99,474. Figure 1 provides the data for all ten provinces, along with how that amount increased between 2018 and 2022 (the figures are not adjusted for inflation). It is worth noting that the least affluent Canadian jurisdictions – Nova Scotia and New Brunswick – have average household incomes less than 70% of that in Alberta.

It is common to group the various sources of household income into two broad categories:

- market incomes, consisting of income from employment, self-employment, and investment and rental income; and,

- government transfers such as EI, CPP, OAS, and social assistance payments.

Employment is the predominant source of market income, generating roughly four-fifths of all such income in Canada. This helps to explain why Alberta is the richest province: it has the highest average wages/salaries in the country. Alberta also leads in labour force participation – defined as the share of the population that is employed or actively looking for work. An additional factor is that Alberta has the highest level of investment per employed person in Canada, which correlates to higher employment incomes. Finally, for most workers and successful entrepreneurs, the income tax burden is lighter in Alberta – resulting in a narrower “wedge” between what people earn on the job and their take-home pay.

Nationally, the typical Canadian household saw after-tax income climb by 17%. Part of this reflects the impact of inflation, which rose significantly in 2021-22 after hovering close to 2% annually for a long period before the onset of the COVID-19 shock. The jump in income also includes the record-high government transfers paid to millions of Canadian households and individuals over the course of the pandemic. When data for the post-2022 period are available, they are likely to show an initial decline in household income given the cessation of the various COVID-related cash transfers to individuals and families.

Politicians concerned about the rising cost of living should not limit their focus to ways to mitigate the effect of these costs on households. They should also pay attention to incomes. This requires looking at the evolving “business climate” and asking whether it is conducive to attracting the private sector investment and entrepreneurial effort needed to give workers more and better “tools” to do their jobs. Unfortunately, this is an area where Canada has been lagging badly over the last decade, with private sector non-residential capital spending recently falling below three-fifths of the level in the United States measured on a per employee basis (as reported by the C.D. Howe Institute).

Without a turnaround in business investment, it will be impossible to boost productivity — and therefore to put real wages and salaries for Canadian workers on a steady upward trajectory. Because employment accounts for the bulk of the market income received by Canadian households, creating an economic environment that fosters and supports business investment in productive assets and activities should be a top priority for the federal government and provincial policymakers.